Tagasaste

KEY POINTS

Tagasaste

- Tagasaste grows well on deep poor sands where annual crops and pastures struggle.

- Tagasaste is only of moderate quality in autumn and animals need lupin supplements during this time to grow.

- Tagasaste can be set stocked with cattle, but only grazed for up to six weeks at a time with sheep.

Author: Tim Wiley, Department of Agriculture, Jurien Bay

Soil types for tagasaste

Tagasaste grows best on freely drained, deep soils such as sands and deep gravels. Tagasaste is well suited to the poor deep sands of Western Australia. It will not do well on shallow soils or where there is waterlogging.

Soil acidity

Tagasaste grows best on soils with a pH between 4 and 7.

Salt and waterlogging tolerance

Tagasaste has a nil tolerance of salt or waterlogged conditions.

Rainfall zones

Tagasaste grows successfully in areas of 300 to 1000 millimetres of annual rainfall.

Cost of establishment

It costs about 100 dollars per hectare to establish tagasaste. This cost varies depending on plant and row spacing, and the insect and vermin control required. There are often additional costs for re-fencing paddocks and providing new water points.

Goat eating Tagasaste

Grazing management

Goat eating Tagasaste

- Tagasaste should be only lightly grazed during the first two years. Once mature, tagasaste performs best with well managed, hard grazing.

- Tagasaste can be completely stripped of all leaves by intensive grazing with sheep as long as it is then allowed to recover.

- While tagasaste can be heavily grazed by sheep for up to six weeks without causing damage, it should not be set stocked by sheep for extended periods as they damage the new shoot buds and can kill plants.

- Cattle can continuously graze tagasaste because unlike sheep, they do not remove the new shoot buds.

- Tagasaste must be hard grazed and/or cut at least once in the first six months of each year. This prevents the plant flowering during the following spring. Flowering results in the leaves being dropped, a slowing of plant growth and a decline in palatability over the following summer.

Tagasaste requires mechanical cutting if it is allowed to get beyond the reach of the animals grazing it (sheep can only graze up to about 1.2 metres). Cutting will cost about 40 dollars per hectare provided it is cut soon after reaching its permissible height. Tagasaste can be grazed at any time of the year. However, the feed quality is best in winter and poorest in autumn.

Feed availability

In the West Midlands, tagasaste can produce between three and five tonnes of dry matter per hectare per year. Highest production will be achieved with good rates of superphosphate (200 to 300 kilograms per hectare per year) and on sites with perched watertables. Very good production can be achieved in low rainfall areas when tagasaste is situated above sandplain seeps. While tagasaste is a true perennial and grows year round, there is a distinct seasonal pattern of growth and feed quality. Tagasaste growth peaks in spring and is lowest at the end of autumn. Tagasaste responds quickly to summer and autumn rain. Cold weather and frost slow tagasaste growth in winter.

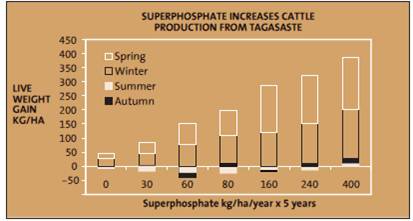

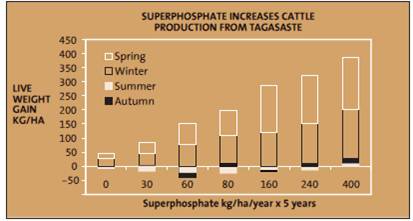

Figure 1: Liveweight gains of cattle grazing tagasaste grown with increasing rates of superphosphate on new land at Dunmar.

Feed quality

Figure 1: Liveweight gains of cattle grazing tagasaste grown with increasing rates of superphosphate on new land at Dunmar.

Fertiliser trials have consistently shown that high rates of phosphorus fertiliser are required for maximum animal growth rates. At the Dunmar Research Station, Badgingarra, an extra kilogram of liveweight per hectare was gained from cattle with every extra kilogram of superphosphate per hectare applied (up to 300 kilograms per hectare). At this site the tagasaste feed production peaked with less than 200 kilograms per hectare per year of superphosphate. Animal production improved with even higher rates of fertiliser (Figure 1).

This occurs because phosphorus fertiliser improves the feed quality of the tagasaste resulting in an increased feed intake by the animals. Similar results were seen at this site when sheep grazed the trial. While growth rates of both sheep and cattle were minimal in autumn, the higher rates of superphosphate meant that animals were still gaining weight slowly rather than losing weight.

In tagasaste, protein, digestibility and most minerals are highest in winter and spring and then gradually decline over summer. During winter and spring, tagasaste is of very good quality and animal growth rates are as good as on any other green feed. No supplements are required at this time of year.

Over summer and autumn the feed quality gradually declines. By late autumn animals on tagasaste will only be maintaining condition. At this time of year protein is the limiting factor for animals despite it never dropping below 14 per cent in the tagasaste leaf. Phenolic compounds are thought to inhibit animal intake and growth rates in autumn.

Lupins

Trials and farmer demonstrations have shown that supplements with a good protein source (such as lupins) will boost animal growth rates in autumn. Supplementation of stock grazing tagasaste with lupins produces a very efficient feed conversion ratio of 4 to 1. That is, one kilogram of liveweight gain is achieved for each four kilograms of lupins fed.

In autumn, mineral concentration in the edible fraction of tagasaste can drop below levels considered necessary for grazing animals. If animals are required to make growth in autumn, supply a well-balanced salt-based mineral lick. Occasionally tagasaste will not be palatable to sheep in autumn. Reasons for the variability between paddocks and seasons are not clear. However,it has been found that palatability is improved if tagasaste is cut mechanically and left to dry for several days.

Out of season prime lambs

In a 1997 experiment at Dunmar Research Station, Merino ewes that lambed in March (Merino x Polled Dorset lambs) were grazed on tagasaste in the short ‘broccoli’ form until late July without supplementary feeding. The lambs grew at 228 grams per head per day during that period while still on their mothers. (This rate of liveweight gain is similar to those on annual pasture). In a similar experiment where the lambs were dropped in December they gained only 100 grams per head per day to July.

Returns from tagasaste

Trials conducted for the Martindale Research Project, found that 100 sheep could be fed for 30 to 40 days on tagasaste that had been locked up for 11 months. This was equivalent to a year round average of eight to ten DSE per hectare per year. This is a considerable improvement for these poor sandy soils that previously carried only one to two DSE per hectare per year with annual pastures.

However, in the trials detailed above, the sheep grazing tagasaste usually only maintained weight in autumn. Lupins are required to enable sheep to grow out at this time of year. One kilogram of lupins should result in 0.25 kilograms of liveweight gain. Therefore, if lupins are costed at 200 dollars per tonne, then an extra kilogram of liveweight gain can be achieved at a cost of 80 cents.

However, in the trials detailed above, the sheep grazing tagasaste usually only maintained weight in autumn. Lupins are required to enable sheep to grow out at this time of year. One kilogram of lupins should result in 0.25 kilograms of liveweight gain. Therefore, if lupins are costed at 200 dollars per tonne, then an extra kilogram of liveweight gain can be achieved at a cost of 80 cents.

If tagasaste is grazed in winter or spring, no supplements are required to grow animals out. Growth rates of animals on tagasaste in winter and spring are similar to those on good annual pasture. This was seen in trials at the Badgingarra Research Station even when all the inter-row pasture was sprayed out and the animals only had tagasaste.

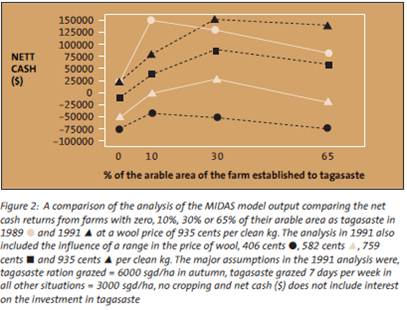

A whole farm analysis based on performances on the Dunmar Research Station has shown that tagasaste is profitable when it is used to replace supplementary feeding of sheep with grain in autumn. The analysis was done on a selfreplacing Merino flock. In the analysis, the whole farm profitability was very sensitive to wool price. However, at any wool price it was profitable to have ten per cent of the farm sown to tagasaste to replace the need for supplementary feeding (see Figure 2).

Species

Tagasaste is a cross-pollinating species and the seed is therefore a genetic mix. There are no true commercial ‘varieties’ of tagasaste.

Landcare benefits

On deep soils (ten metres) tagasaste can use all the season’s rainfall, thereby lowering water tables. Where tagasaste can tap into a perched, fresh watertable it can use twice the average rainfall.

Further reading

Angell, K. and Glencross, R. (1993). Tagasaste and Acacia saligna establishment using bare-rooted seedlings. Department of Agriculture, Bulletin No. 4262.

Lefroy, E. C.; Oldham, C.M. and Costa, N.J. (1997). Tagasaste Chamaecytisus proliferus. Proceedings of a workshop to review tagasaste research in Western Australia. Centre forLegumes in Mediterranean Agriculture (CLIMA). Occasional Publication No. 19,CLIMA, Western Australia.

Wiley, T.; Oldham, C.; Allen, G. and Wiese, T. (1994). Tagasaste. Department of Agriculture, Bulletin No. 4291.