Setaria grass

Setaria grass

KEY POINTS

- There is a range of subtropical perennial grasses available for most soil types.

- Excellent production can be achieved where there is a shallow water table.

- With good management, animals can grow on perennial grass pastures over summer.

Author: Tim Wiley, Department of Agriculture, Jurien Bay

Soil types

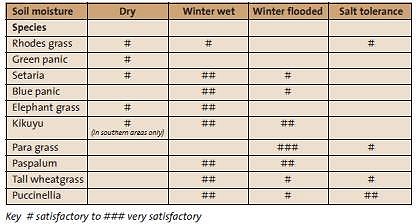

Subtropical perennial grasses will grow on almost all soil types. Differences within species are due mostly to their response to soil moisture. It is recommended to sow a mixture of species to cover any variations in soil type (see Table 1 for the broad growing environments of different species).

In general, subtropical perennial grasses should not be sown on areas that are to be used for winter cropping as they may be difficult to drill seed through and are expensive to remove. However, satisfactory results have been reported on the south coast with canola sown into perennial grass. On two farms where kikuyu grass was sprayed before cropping, a good regeneration of the grass followed the canola crop, with the slow-growing kikuyu grass having little effect on the canola crop over the winter or on its subsequent yield.

Acidity

There are no quantitative data on the effects of soil pH on subtropical perennial grasses in Western Australia. Experience suggests that problems for subtropical perennials would only be encountered at the extremes of acidity or alkalinity. Soil pH is likely to be more of an issue for the companion legumes.

Salt tolerance

Species such as puccinellia, tall wheat grass, Rhodes grass and para grass have good salt tolerance, but establishment is difficult on salt-affected areas. Exposing potentially saline areas in late spring by spraying and grazing the areas in readiness for seeding with tropical grasses, can accelerate the surface accumulation of salt, adding to the difficulties of establishment.

Climate

Subtropical perennial grasses are summer active and winter dormant. All these grasses will be burnt by frost, but will survive. The grasses will grow and survive in all regions of Western Australia. Their production is more dependent on their position in the landscape and the pattern of rainfall, than on the average annual rainfall. These pastures respond well to summer rainfall events.

The seed of these grasses will not germinate if it is too cold. The temperatures required for germination will not be achieved until late September in the northern section of the agricultural region and by early to mid October in the south of the agricultural region.

Cost of establishment

Subtropical perennial grasses are difficult to establish and require total weed control before sowing. They should be sown in spring when temperatures are rising. The seed must be placed on the surface and then pressed or rolled in.

Experienced farmers estimate that these grasses can be established for about 100 dollars per hectare. They also suggest that it is worth considering withholding grazing during the establishment phase. The grasses are safe to graze once the roots are well established and the plants cannot easily be pulled from the ground. Failure to establish the grasses at the first attempt will increase overall costs considerably.

Table 1. Subtropical perennial grass species and their use in the landscape

Table 1. Subtropical perennial grass species and their use in the landscape

Grazing management

Rotational grazing is probably the best way to manage the perennial grasses over summer. However, most species will persist under set stocking. Whatever the grazing method, grazing pressure needs to be maintained on these grasses over summer and through autumn because if they are under-grazed at this time they will deteriorate in quality and palatability.

On the highly productive wet areas, farmers are using temporary electric fences to cellgraze these pastures. They may graze the grasses at up to 1000 DSE per hectare in a cell for up to a week. Generally the rotation is set up so that there is a four to six-week rest between grazings. However, on the south coast,continuous grazing of kikuyu grass over summer at high stocking rates has proved to be successful.

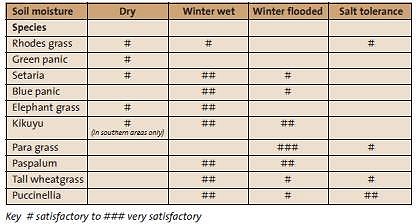

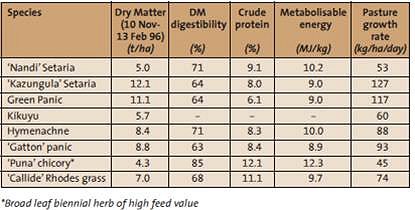

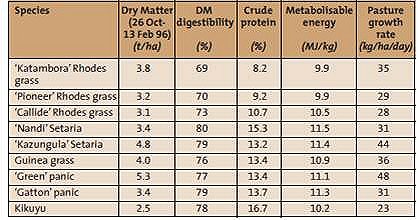

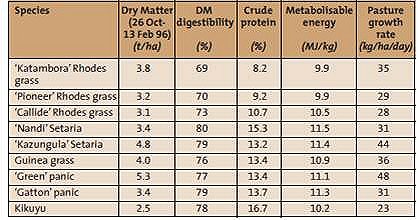

Table 2. Perennial grass production and quality on a winter flooded white sand at Cataby (13 February 1996)

Subtropical perennial grasses should be grazed down hard to ground level by the end of autumn. This allows the annual legumes in the pasture to make good growth at the break of season. With a well-managed pasture mix, it should be difficult to see perennial grasses below the clovers in winter and spring. Winter grazing should aim to optimise the annual legume component of the pasture.

Feed availability

The amounts of feed produced by subtropical perennial grasses depends on the supply of nitrogen and soil moisture (see Tables 2 and 3).

These grasses are very drought tolerant and can survive without summer rain. On sites with shallow perched watertables (less than 2.5 metres) they do not require summer rain to be very productive.

Perennial grasses have a high requirement for nitrogen for optimum production. Where there is adequate soil moisture they will respond to up to 400 kilograms per hectare of nitrogen. If bagged nitrogen fertiliser is applied it should be through split applications while soil moisture persists. However, the most efficient system for meeting nitrogen requirements is to have a productive companion legume.

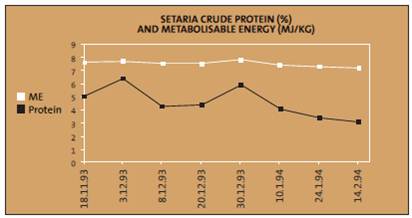

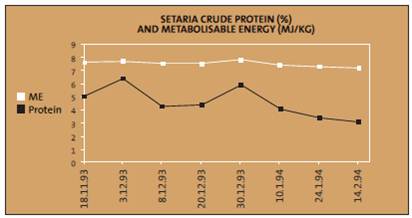

Figure 1: Decline in crude protein content of Setaria over summer on a poor sand (Badgingarra 1993/4).

Figure 1: Decline in crude protein content of Setaria over summer on a poor sand (Badgingarra 1993/4).

Feed quality

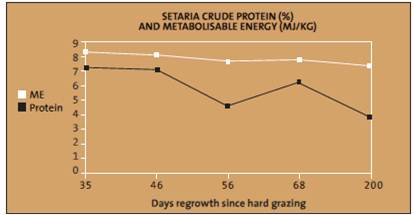

The quality of feed provided by subtropical perennial grasses depends on the availability of moisture, the time of year (Figure 1), the amount of nitrogen available, stage of regrowth (Figure 2) and the grazing pressure on the grasses.

There is a general trend for the quality of feed provided by perennial grasses to decline gradually over summer. Rotational grazing will provide a pasture with a large proportion of young leaves with high nutritional value. At Badgingarra, the sheep gained weight even though the analysis of the whole plant showed that it was of very low feed quality. In this case, the sheep selectively grazed the young grass shoots and these were of higher quality than the rank parts of the grasses.

Figure 2: The quality of Setaria declines as the plants regrow from hard grazing (Badgingarra 1993/4).

Both protein and energy can become limiting. Animals should be monitored and a supplement such as lupins fed as required. Companion legumes will also boost the quality of the total feed supply when they are green. On wet areas balansa or persian clover, Cadiz serradella, and strawberry or white clover are likely to be suitable for growing with the perennial grasses. On drier areas, serradellas, subclover, arrowleaf clover,biserrula or blue lupins may suit depending on the location.

Table 3. Perennial grass production and quality on a valley loam at Moora (13 February 1996)

Table 3. Perennial grass production and quality on a valley loam at Moora (13 February 1996)

Grazing performances from subtropical perennial grasses

Stocking rates for subtropical perennial grasses vary from site to site depending on the availability of subsoil moisture and summer rain. The following examples outline the sheep carrying capacities of some of these grasses. However,presently there is little documentation of animal performance on these subtropical grasses in the agricultural areas of Western Australia.

David Monks at Badgingarra runs 1800 weaners on 30 hectares of kikuyu grass and strawberry clover on a low lying wet sand throughout each summer. He uses a cell grazing system to rotate sheep and avoid Barbers Pole worm problems. These sheep do not see dry feed until they are one year old. In other words, it is not until they are in their second summer that they go on to dry annual pastures for the first time.

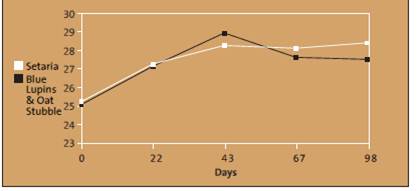

On a neighbouring farm, Dale Park ran seven weaners per hectare for 114 days over summer on Setaria grass. He compared liveweights on Setaria with a district practice of grazing Blue lupins and oat stubbles (Figure 3). This was a deep, poor white sand and there was no summer rain. Weaners on the Setaria gained 30 grams per head per day without supplementary feeding.

At Peter Nixon’s, West Gillingarra, weaners were run at 265 per hectare for 30 days on a strawberry and balansa pasture on wet sand over summer. These weaners put on 150 grams per head per day or 1100 kilograms of liveweight per hectare.

Figure 3: Liveweight (kg) of weaner rams grazing Setaria or Blue lupins and oat stubble from 8 December 1993 to 31 March 1994 (Badgingarra).

An experiment at Manypeaks on the south coast showed the benefits of grazing kikuyu grass-based pastures compared with annual pastures. The main benefits were in carrying capacity (that is, increased stocking rate and/or less supplements fed) and in wool quality, with stronger cleaner wool grown on the kikuyu grass.

Other considerations

Barbers pole worm can be a serious problem on wet areas with perennial pastures, and other worm species may be a problem in the milder climates. To help reduce this problem, the pastures should have a long spell before summer grazing.

Sheep should be adequately drenched before grazing these grasses. Long spells (for example, six weeks) between grazings in summer, will, through heat and desiccation, help reduce viable worm eggs available on the pasture. Where there is concern, regular sampling and assessment of the worm status of sheep should be undertaken and further advice sought from a veterinarian.

In some areas there have been some problems with selenium and cobalt deficiencies on the wet sands over summer. Farmers should apply these trace elements with fertiliser or directly to the animals (see

Barbers Pole Worm

Farmnote 110/94,‘Trace element deficiencies in sheep and cattle’). Horses should not be grazed on pure Setaria pastures as they can develop the ‘Big Head’ syndrome caused by a calcium imbalance due to high levels of oxalates in Setaria.

Problems with oxalates in other species of animals have been reported in the eastern states but not in Western Australia. These types of problems are usually avoided where there is a mixture of pasture species.

Landcare benefits

The subtropical perennial grasses will increase water use and prevent both wind and water erosion.

Further reading

Miscellaneous Publication 2/98. Greathead K.; Sanford P. and Cransberg L. (1998). Perennial grasses for animal production in high rainfall areas of Western Australia. Department of Agriculture.

Farmnote 20/99. Perennial grasses : their role in the Ellen Brook Catchment

Farmnote 11/95. Kikuyu, the forgotten pasture

Farmnote 110/94. Trace element deficiencies in sheep and cattle

Farmnote 8/92. Chemical manipulation for irrigated kikuyu grasses.