Pasture mass

Pasture mass

Pasture mass can either be assessed by cutting, drying and weighing representative pasture samples or by the use of tools of varying levels of sophistication. The various southern state PROGRAZE® manuals give full descriptions of the methodology involved in assessment by cutting, weighing and drying.

Pasture assessment tools save much time in collection, and are considered to be the only practical method for use when day-to-day assessments are being made. There are three broad groups of tools to measure pasture mass:

• Pasture rulers or ‘sticks’ that measure pasture height are simple, cheap and easy to use. Heights are easily converted to an estimate of kg green dry matter/ha via look-up tables.

– Pasture density also needs to be estimated and used as a correction factor when growing or mature pasture is less than 100% of ground cover. See methodology for assessing ground cover and pasture composition below which can be used to estimate the percentage density of pasture.

– The measurements also give a guide to the mass of dry standing feed, but usually underestimate the reading. PROGRAZE® notes describe a method to adjust.

– With experience, you can use the height assessment method to gain reasonably accurate estimates of mass, especially when periodically checked against assessments made by cutting and weighing.

• Rising plate meters measure total pasture mass, green and dry standing feed, and are based on a plate that rises up a probe depending on the amount of compressed pasture material between the plate and ground.

– Sophisticated models are available that will collect and store field measurements to average readings across a paddock or a number of paddocks.

– They are available from a number of commercial outlets, and price generally depends on the degree of automation of collection.

– Generally slightly cheaper than electronic probes, and may be preferable when frequent automated assessment of pastures with significant levels of non-green pasture is needed.

• Electronic pasture probes measure dry matter of green material only.

– They are quick, easy to use and usually fully automated, including the capacity to directly download readings into office based computers.

– Some also allow collection of user defined and read assessments such as ground cover or phenology.

– Their accuracy declines if there is any free moisture present in the pasture, eg after rain or heavy dews.

These are normally the most expensive of the three groups.

• Satellite imaging is currently under experimental assessment to measure the growth and amount of pastures across southern Australia.

Numerous commercially available meters and probes can be found on the Internet (search for “pasture + meter”). Most rural supply firms will also help locate commercially available models.

Ground cover

Ground cover includes existing pasture, weeds and other herbage as well as litter. To estimate ground cover, stand in a representative part of the pasture with your feet half a metre apart. Picture a half metre square in front of you, and looking vertically into the pasture, estimate the percentage area covered by plant matter and litter. Walk over the paddock and repeat the assessment at about 30 random sites. Record and average the results to accurately determine the percentage of ground cover.

Pasture composition

The described methodology will assess the frequency of both individual species (eg perennial ryegrass) and species groupings (eg perennial grasses).

• Cut a 30cm length of 1cm-thick dowel, and either point or drive a nail into both ends.

• Throw the stick ahead at random intervals while walking across the pasture being assessed.

• After each throw identify and record the pasture species or species group that is touching or immediately below the points at both ends of the throwing stick.

• Repeat 50 times (depending on the evenness of the pasture) to give 100 readings for a double-ended stick.

• Total the number of hits for each species or group and divide by 100 to give % frequency (or composition).

• Normal groups used are perennial grasses, legumes, annual grasses, weeds and bare ground.

• PROGRAZE manuals include an example of a recording sheet that simplifies and speeds up the collection and recording process.

Pasture phenology

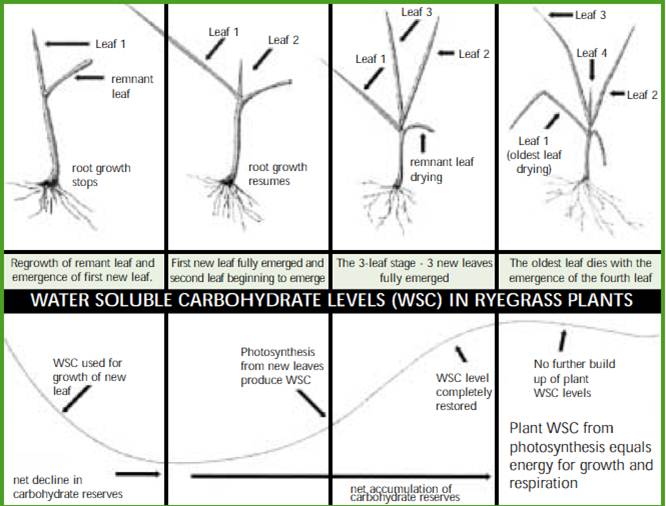

Assessment of phenology is made for target species and involves the examination of individual tillers from perennial grass clumps to count the number of new leaves on each tiller. The number of leaves is a good indicator of the start of senescence (dying) of the oldest leaf on each tiller. Generally the ideal number lies between three and four tillers, however the number of leaves varies from species to species. Figure 1 indicates the correlation between levels of water soluble carbohydrates and leaf number for perennial ryegrass.

Figure 1: Regrowth of a perennial grass tiller

Rate of run-off or surface ponding

The run-off rate is estimated by taking a full nine-litre plastic garden watering ‘can’ and, with the sprinkler top in place, steadily pouring the water evenly over a representative one metre square soil surface (soil and plant material). Finish pouring after 60 seconds. Any run-off or ponding existing at the end of this period is evidence of poor infiltration rates but will depend on the current moisture content of the soil.

Pasture quality

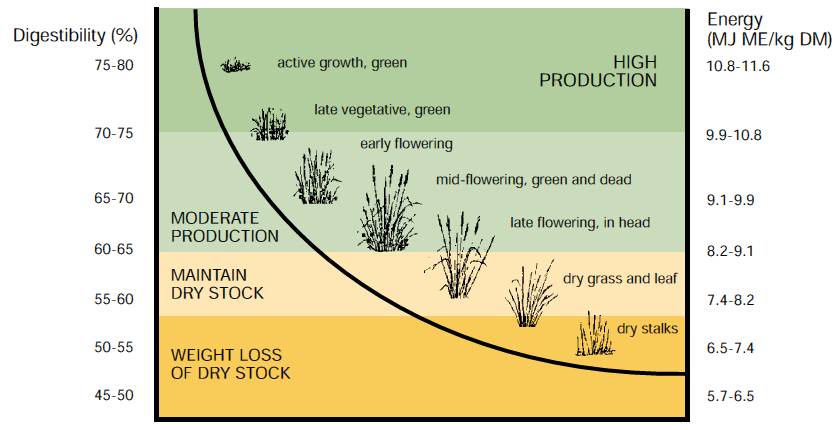

Assessment of pasture quality (energy content) normally requires full laboratory analysis. Field observations provide a useful guide to energy content in MJ ME/kg DM. Actively growing green material is normally in the range of 11.0 to 12.0 MJ ME/kg DM. Actively growing legumes normally have slightly higher energy content (+ 0.5 MJ ME/kg DM) than perennial grass. Therefore pasture that is 100% green, has legume and perennial grass composition within the limits of 20 to 30% legume and 60 to 70% grass and the oldest leaf of the dominant grass has not started to senesce, can be assumed to have energy content greater than 11.5 M J ME/kg DM. Figure 2 below gives a guide to energy decline as temperate pastures mature.

Figure 2: A guide to digestibility decline as temperate pastures mature