Importance of feather loss.

Importance of feather loss.

Feather loss generally is a natural process with fowls - moulting to replace old feathers. However, aside from the aesthetics, feather loss is an important indicator as it may indicate problems in the management of the flock. These could be nutritional, medical, environmental, social or welfare in nature. Most feather loss remedies require changes to flock management.

Economically, plumage deterioration results in increased food consumption and hence less efficient egg production. A substantial improvement in plumage condition brings economic value to the producer.

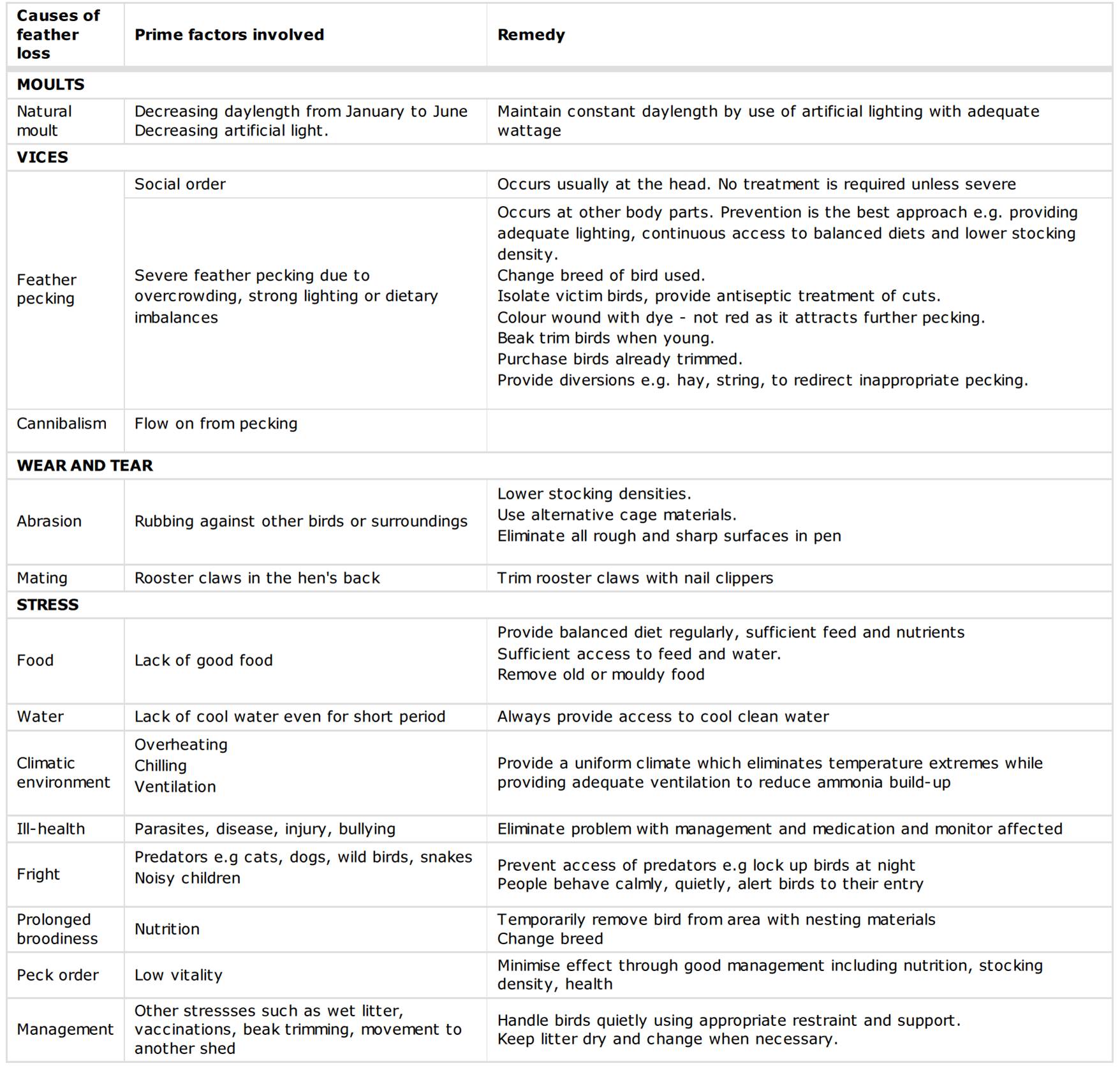

The table below summarises various causes of feather loss and the remedy required.

Moulting.

This is a physiological phenomenon, which consists of the shedding of feathers, followed by replacement with new feather growth. It is usually accompanied by a reduction in egg production or even a complete halt (see link at end of article for further information).

Natural moulting.

Prior to obtaining adult plumage, fowls at several stages during their life undergo a number of moults where the old feathers are replaced by new.

First moult - when down is replaced by the first juvenile plumage, occurring at 6-8 days and ending at 4 weeks.

Second moult - when the first juvenile plumage is replaced by the second juvenile plumage. This occurs over a number of weeks starting between 7 and 12 weeks of age.

Third moult - generally occurs in the hen at 16 to 18 months, however this depends on the time of year that the bird started laying. This moult is of most importance for producers.

In the laying hen, natural moulting occurs when the days are getting shorter, i.e. from January to June. Hormones secreted by the thyroid gland determine the course of the moult. The use of artificial lighting to maintain a constant daylength can be used to avoid this natural moult. This works principally by altering the bird’s daylength ‘hormone-clock.’

Moult characteristics.

Male birds moult before females. Shedding is first observed on the head and neck, then the breast and finally the tail and wings. Moults can be partial (occurring on particular body parts) or complete. The extent of moulting depends upon the breed and the individual bird. The length of the moult is variable; poor layers reconstitute their plumage in 6-8 weeks while good layers following a pause in laying can replace their feathers in 2-4 weeks.

Physiologically, the stop in egg production allows more dietary protein to become available for feather production which are primarily proteins themselves. Oestrogen, a hormone released during egg production, retards feather formation. Cessation of lay reduces oestrogen levels so that feather formation is enhanced.

Vices.

Feather-pecking.

Feather loss can be caused by vices such as feather-pecking. Once established it is difficult to control and prevention is the best remedy.

Social order pecking occurs primarily at the head and is not severe. Severe feather pecking due to overcrowding, lighting problems, unbalanced diets and possibly lack of diversionary activities will injure the bird.

Cannibalism.

Cannibalism.

With feather-pecking any subsequent injury with drawing of blood will attract further pecking leading to cannibalism. To prevent cannibalism it is best to isolate the sick or victim bird from the flock or cage. The injured bird should have cuts treated with antiseptic powder and the wound should be coloured with a dark (not red) food dye or Stockholm tar to reduce further pecking attacks. Alternatively the victim birds can be dusted with a repellent. Once healed, the bird can be carefully reintroduced to the flock and monitored to ensure pecking (cannabalism) is not repeated. Beak-trimming or purchase of beak-trimmed stock will reduce the likelihood of feather-pecking and cannibalism, especially if problems associated with lighting, stocking density and nutrition have been corrected. It has been observed that some breeds are more likely to feather-peck than others.

Wear and tear.

Abrasion.

Feather loss is also caused by rubbing against other birds or surroundings, particularly if the birds are closely confined. To reduce feather loss, stocking densities should be lowered and all sharp and rough surfaces in a cage eliminated. Alternative cage materials may also assist, as feathers wear away at different rates when rubbed against different types of cage materials.

Mating.

During mating the hen may lose feathers by the rooster treading the hen. The feathers are torn from the hen’s back by the rooster’s claws. To reduce this feather loss, the rooster’s claws need to be trimmed with nail clippers. The rooster’s spurs can be trimmed to about 1.5 cm in length with secateurs.

Stress.

A number of factors lead to stress, which can contribute to a cessation of egg production and the onset of a moult. Generally a lack of food or water is the most frequent stress causing feather loss. Poorly balanced diets or mouldy feed can also bring on moulting. Lack of cool, clean water, even for a short time, can cause birds to moult. To minimise this, an emergency backup water supply is advisable. Feather loss can also be caused by chilling, overheating and poor ventilation. A good housing environment will eliminate temperature extremes and still provide good ventilation for the birds. Ill-health either from injury, disease, parasitism or bullying may also contribute to moulting. Good stockmanship including regular monitoring of birds will minimise stress and reduce further feather loss.

Table 1. Prime causes of feather loss and their remedy.

Author.

John Kopinski.

![]()