Fig 1 Fabric Containing Dark Fibres

Introduction

Dark fibre in white wool is a serious fault that is heavily penalised when identified. Australia has a valued reputation for supplying wool that generally has low dark fibre content.

This advantage relies on farmers and woolclassers, with guidance of the AWEX Code of Practice, to ensure that affected wool is separated and appropriately described. Should dark fibre content go unrecognised in manufacture then the costs of batch rejections and product mending that result can be prohibitive and this affects the value and competitiveness of wool fibre.

There are several sources of dark fibre of which sporadic “clumpy” types are unable to be reliably sampled (e.g. small spot) in baled wool. Distinct spots of dark wool and urine stain can usually be readily seen and controlled on-farm while for inherited isolated pigmented fibre there is information about related visible pigmentation types on sheep that can be used as indicators of risk. In general, Merino wool is of relatively low risk of pigmented fibre though potential for improvement remains.

Australian Wool Innovation Ltd (AWI) initiated a research program (AWI 2003) to develop technology for presale measurement of wool bales for dark and highly medullated fibre (AWTA et al. 2004; Fleet et al. 2007) together with a complementary information system for specifying these risks. The priority for this program developed with industry concerns about changes in Merino crossbreeding that involves high-risk coloured and highly medullated types (e.g. Awassi, Karakul, Damara and Dorper). The Federation of Australian Wool Organisations, with support from AWI, introduced vendor declaration and the Dark and Medullated Fibre Risk Scheme to provide wool buyers and processors with guidance about the content of dispersed dark andmedullated fibres in wool lots (http://www.woolindustries.org/dmfr.htm ; AWEX 2007).

Sources and control

Fig 2. White polypropylene in wool top and dyed fabric.

NON-SHEEP dark fibre contaminants are controlled by quality management, minimising the risk of exposure of sheep to such fibres. This involves avoidance of use or precautions (cleanliness) in the paddocks, yards and shearing sheds. Potential contaminating fibres include bale twine, fertiliser bags, feathers, string or rope, rags and clothing and other animal fibres (e.g. alpaca, goat, cattle, dogs, cats and rodents).

Non-approved pack material or white synthetic fibres (except nylon), as contaminants of wool cause the opposite problem to dark fibres, as they may not accept dye (Figure 2). Vegetable matter can also cause problems but this fault is measured presale and processors can plan to minimise effects through carbonising, carding and combing. Detection of non-sheep dark fibres (e.g. twine) within the presale test for vegetable matter leads to the wool lot being withdrawn from sale and rehandling costs incurred (passed back to the grower) to locate the material.

SHEEP dark fibres include those transferred from coloured or partly coloured sheep and those grown on the white sheep. Highly medullated white fibres transferred from certain breeds or in Merino crossbreeding situations can also cause problems as these fibres can have restricted dye uptake and show as faults in coloured wool products. Dark fibres produced by sheep may be caused by urine stain or melanin pigment. Other staining effects (e.g. fleece rot, faeces and blood) will generally not darken the fibres enough to cause a problem except when there is bulk discolouration (e.g. colour line). Spray marks and brands can sometimes lead to dark fibres due to inappropriate application (e.g. close to shearing). Apply spray marks to the face rather than wool-bearing areas.

Urine stain

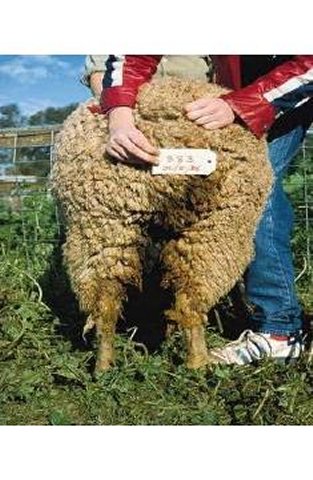

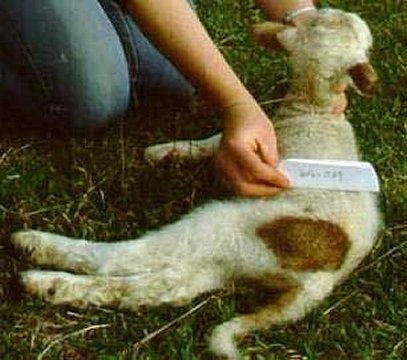

All sheep can produce urine stained fibres. Skirted fleece from wethers or rams is lower risk (stain on belly wool) than for ewes. CSIRO research has determined that wool exposed to urine should be removed from all sheep prior to shearing (Figure 3 and 4). Crutching to remove stained wool carried out within 3 months of shearing greatly reduces the risk of excessive urine stained fibres. Longer periods are likely to result in dark fibre concentrations exceeding 100 per kg of top. If precautions are not taken to effectively control urine stain then efforts to reduce other dark fibre sources could provide limited advantage for that clip.

A dark fibre decision scheme, originally proposed by CSIRO primarily for identifying urine stain risk, has been adapted for Merino fleeces and pieces wools to include contacts with breeds of high-risk for pigmented or highly medullated fibre. The information system to inform buyers and processors of these contaminant fibre risks, through catalogue advice and presale test reporting, was introduced to wool marketing in July 2004 (further details at http://www.woolindustries.org/dmfr.htm and AWEX 2007).

Fig 3. Ewe with heavy urine stained wool around the crutch.

Fig 4. Urine stained fibres can be minimised by the removal prior to shearing of wool likely to have been exposed (crutch of ewes and pizzle wool of rams and wethers) to urine.

Pigmented fibres

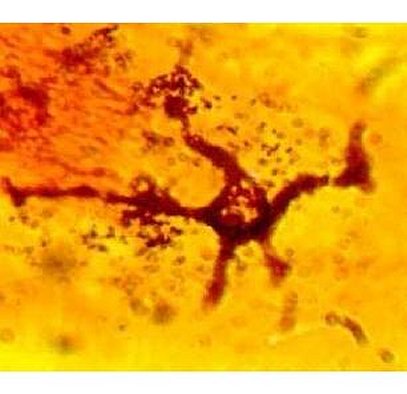

Melanin is the natural pigment produced in the skin by special cells called melanocytes (Figure 5). These pigment cells transfer coloured granules to surrounding cells via finger-like projections. When pigment cells are present in wool or hair follicle bulbs then a pigmented fibre usually results. Genes that the sheep inherit primarily determine the location, number and activity of pigment cells.

Fig 5. Pigmented cell (melanocyte).

Sheep breeders have selected genes that inhibit the development of pigment cells within wool and hair follicles so producing white coats. The genes involved are currently not confirmed though several potential candidates causing similar effects in human, mice and other livestock are recognised (Fleet et al 2004; Fleet 2006). Until researchers can characterise the DNA, or identify genetic linkages that can be used as aids in selection, breeders will have to accept the inefficiencies of reliance on phenotype alone.

Fig 6. Developing pigmented wool follicles.

It is important to know the types of pigment most relevant to the risk of dark fibres in wool. Increasing buyer attention to dark and medullated risks will increase the importance of the reduction of these contaminant or inherited fibres on-farm. SARDI has identified various types of visual pigmentation on Merinos on which selection can focus to improve wool quality (Fleet 1996).

Recessive black lambs

An occasional black lamb can arise in Merino selfreplacing flocks when a ram carrying the recessive gene is used within a flock. The inheritance appears simple (i.e. from carrier parents on average one in four progeny will be black). Pigment primarily develops during pregnancy. The first evidence of pigment cells in the skin of a recessive black foetus can be seen between 50 and60 days after conception (Fleet et al 2004). By 70 days, pigment cells are seen being incorporated into budding wool follicles (Figure 6).

Fig 7. Twin lambs (one black and one white from carrier parents.

Different recessive black patterns occur due to genetic variation within the primary gene and to other genes that have modifying effects; such as white spots (Figure 7 and 8). Black around both eyes is a distinct feature of extensively white spotted black lambs (Figure 8). Occasionally a coloured lamb may also be born with a brown (moorit) coat and this is the effect of another interacting recessive gene. The frequency of the gene and carrier sheep responsible for black lambs varies between flocks.

Fig 8. Black lamb with extensive white spotting.

When the gene frequency is low many lambs may be born before use of a carrier ram is recognised. About half of the progeny of a carrier ram will be carriers. In a ram breeding flock all known carriers and their progeny should be culled. The gene for black lambs has no effect on isolated pigmented fibres in the wool grown on white carrier sheep. However, coloured sheep left in white flocks can lead to transfer of dark fibres to white sheep or wool. Coloured lambs and their rearing ewes should be separated from the white flock.

Fig 9. White lamb with black random spot on the side. Also note the tan halo-hair on the back-of-neck.

DNA parentage testing services can be used to identify which ram in a syndicate mating has fathered a black lamb. Specific DNA test(s) could allow the reduction or elimination of genetic variation responsible for recessive black lambs. Research by Macquarie University, to which SARDI collaborated, determined that this genetic variation involves chromosome 13. Research by CSIRO (involving the SheepCRC, AWI and MLA) and others has since found the ovine gene responsible (Agouti or ASIP) to be complicated; making the development of a specific test to identify white carriers difficult. The most recent research findings are reported by Royo et al (2008) and Norris and Whan (2008).

Random spot

Fig 10. White lamb with a tan random spot. Note also the tan ear tips and tan halo-hair back-of -neck.

Distinct patches of pigmented fibres can occur anywhere (randomly) on the coat. The spots are usually black or grey (Figure 9) but can be brown or tan (Figure 10). Affected sheep usually have only one random spot that can range in size from small to large and obvious. If there are multiple spots on the sheep, or both sides of the face are affected (i.e. both eyes), the sheep may be recessive black

Random spots appear to have a complex determination but affected sheep can increase with other pigmentation types (e.g. leg fibre pigment). These spots, including affected wool that is missed at shearing, can be important sources of dark fibres. The wool fibre spots can fade in early life, making subsequent detection difficult, yet still present a large number of hidden pigmented fibres. Affected sheep should be shorn separately and culled (for slaughter) as soon as possible from the white flock.

The entire fleece or at least the pigmented spot(s) should then be placed in a container for pigmented wool (BLK). The white wool from these fleeces has a risk of residual pigmented fibres so needs to be kept separate from low risk wools and the Y suffix can be used instead of BLK.

Fig 11. Isolated pigmented fibre in a wool staple.

Isolated pigmented fibres

Some white fleeces contain isolated pigmented wool fibres (Figure 11 and 12). Even when these fibres are numerous, identification is unlikely from visual inspection of wool. In Merino sheep visible hair pigmentation is usually less frequent than skin or hoof pigmentation. Culling types of visible hair pigmentation has been shown by SARDI to be effective at minimising the risk of isolated pigmented wool fibres in the hogget fleece. In some of the flocks, one or two types of hair pigment (e.g. pigmented birthcoat halo-hair and leg fibres) may be important, while in others several types of fibre pigmentation may have additional effects. These types of hair pigment in, or bordering, the fleece can also be direct contaminants.

Fig 12. Isolated pigmented wool follicle in skin.

AWI and MLA (2007) produced a Visual Scores booklet to assist breeders in recognising and recording pigment and that information may ultimately help develop DNA tests to assist sheep selection. (http://www.sheepgenetics.org.au/merinoselect/)

Fig 13. White foetal lamb skin at 85 days after conception showing developing wool follicles (F) and pigment cells (M). In this case, isolated pigmented wool fibres could develop. Note the differences with Figure 6 for a black Merino foetus.

In contrast to the recessive black foetus there is usually an apparent complete absence of pigment cell precursors in the developing foetal wool-bearing skin of a white Merino lamb. Pigment cells were usually not evident in the skin of white Merino lambs until late pregnancy or after birth and miss inclusion in developing wool follicles. In certain cases, some pigment cells reach the skin while primary and original secondary follicles are initiated (64 to 100 days) and isolated pigmented wool fibres may then develop (Figure 13).

However, the route of entry via the epidermis is restricted since colonisation in this tissue is inhibited at that time. The genes affecting pigment cell migration, colonisation and longevity in sheep remain to be confirmed and these advancements would likely assist the development of diagnostics for specific selection of the most effective and acceptable genetic variation.

Risk of isolated pigmented wool fibres in Merino sheep is confined mainly to young sheep of less than 2 years of age. Sheep between 2 and 6 years of age seem likely to have a low risk of isolated pigmented wool fibres present from early development. This change with age involves the loss of pigment cells from wool follicles (“greying”).

Fig 14. New-born lamb with just a few tan halohairs on the back-of-neck.

Birthcoat halo-hair

Lambs may be born with pigmented halohairs. These hairs tend to be concentrated on the back-of-neck making visualrecognition practical for newborn lambs. There may be single, few or many hairs (Figure 14 and 15) evident on affected lambs. The risk and level of isolated pigmented wool fibres increases with degree of pigmented halo-hairs evident on the backof-neck.

Heritability of this type of pigmentation is high and should be able to be reduced by selection. However, a problem with reducing this pigmentation and associated isolated pigmented wool fibres is the temporary presence of halo-hair on the lamb coat. Gradual shedding of the birthcoat halo-hairs soon after birth means a later inspection at lamb marking may only reveal high degrees on early born lambs. The hairs are usually tan coloured. Mark for culling the affected lambs, at least those with distinct pigmented halo-hair, and separate for shearing last and send to market (for slaughter) as soon as practical.

Fig 15. Lamb with a distinct patch of tan halo-hairs on the back-of-neck. Note also the tan margins on ears.

Leg hairs

Pigmented hair spots and patches occur on the legs of some sheep. The spots tend to be tan coloured in Merinos and can vary in degree from one or a few spots, and from speckled areas to large patches of pigmented hairs (Figure 16 and 17). on the back-of-neck. Note also the tan margins on ears.

There is symmetry of spotting so the pigmentation tends to be evident on all legs or a pair of legs. The spots tend to be most prevalent on the back of the rear legs. Leg hair pigmentation is highly heritable in Merinos and an identifiable gene appears to be involved in the elimination of this type of pigment; presence being the dominant feature. When leg hair pigment is present other types of pigmentation tend to be increased. This includes pigment in nose-lips, skin and hooves, random fibre spots and isolated pigmented fibres in the fleece.

Pigmented leg hair tends to become more prominent as the lamb matures and then remains stable during adult life. This persistence of pigmentation and the effects of the identifiable gene can allow effective culling and a minimal occurrence in Merino flocks. Inspections can be made at lamb marking or sheep classing, but this pigment is best observed when the wool is removed from the legs at crutching and shearing. Ask the shearers to check for this pigment. Mark for culling the affected lambs, shear them last and send to market (for slaughter) as soon as practical.

Fig 16. Single spot of pigmented leg hairs.

Fig 17. Patches of pigmented leg hairs. Note streaks in hooves.

Other types of hair pigment

Other types of hair pigment on white sheep that have shown associations with isolated pigmented wool fibres can occur on the horn sites, face, ears and eyelids. At least those lambs/sheep with distinct fibre pigment should be marked for separate shearing and culling (for slaughter). The heritability of pigmented horn site hairs is high while for face hairs it may be low. These pigmented hairs tend to arise and disappear with leg hair pigment. Like leg hair pigment they become more prominent as the lamb matures and remain stable during adult life (Figures 18 and 19).

Fig 18. Pigmented hairs on horn sites of a lamb.

Fig 19. Pigmented hairs on the face and horn sites of an adult.

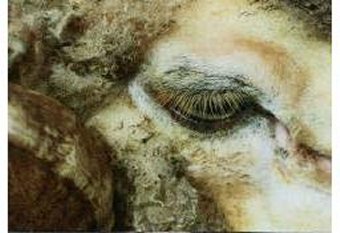

Merino sheep can have a mixture of tan and white eyelashes. In some cases, these tan hairs are very prominent (Figure 20). Heritability is high in Merinos. It is the high degree of expression (>75% pigmented) that has been associated with risk of isolated pigmented fibres.

Fig 20A. Prominent pigmented eyelashes on a lamb.

Fig 20B. Prominent pigmented eyelashes on a ram.

Two forms of coloured ear fibres exist on white Merinos. On lambs, the pigmented ear hairs are tan coloured and affect the tips or margins of the ears (Figure 21). These fibres fade as the lamb matures. On hoggets and adults, diffuse spots of black hairs may have developed, especially on sheep with other pronounced fibre and skin pigmentation, and these are likely to remain during adult life (Figure 22). Heritability of both types of ear fibres may be low to moderate in Merinos. The association between tan ear fibres on lambs and isolated pigmented fibres appears to be less than for the other types of hair pigmentation.

Fig 21. Tan hairs on the ear tips of a lamb.

Fig 22. Black hairs on an adult ear.

Skin and hoof pigment

Skin and hoof pigmentation of varying degrees occurs frequently among Merino sheep. There may be some reduction of pigmented wool fibres arising from selection against skin and hoof pigment. However, it is considered more efficient to check for hair and wool pigmentation of primary concern and select against these types. It should be recognised that the various types of pigmentation are positively related. Selection against fibre pigmentation will tend to reduce the other more common pigmentation types (skin and hooves).

There seem to be little benefit to be gained in wool quality, given the current knowledge, from selecting against skin and hoof pigmentation on Merino sheep that remain in the flock after close attention and culling of wool and hair pigment. However, each sheep breed organisation has specific requirements for the amount of skin and hoof pigmentation desired.

In the Merino there has been a traditional selection against all types of pigmentation. Pronounced nose-lips skin and hoof pigment would generally not be tolerated in Merinos and tends to accompany unwanted hair pigmentation. In contrast, for other breeds like the Corriedale and Romney, the preference has been for prominent nose-lips skin and hoof pigment.

Old-age wool fibre spots

As white sheep age there is potential for changes within the wool-bearing skin that can make epidermal pigment cells very active and move to wool follicles leading to pigmented fibres. This change can be induced by additional shearings or repeated exposure of bare-skin to sunlight or artificial ultraviolet light. The first sign is a round black-grey skin spot in the fleece region that subsequently produces black-grey pigmented wool fibres. The increase with age is exponential, with the pronounced rises occurring after 5 years in the Merino flock studied (Fleet 2006).

Fig 23. Old-age – black skin spots with pigmented wool fibres. The sheep was 8.5 years old and shorn 3 months previously.

Very old Merinos sometimes have many age spots and produce fleece wool with high concentrations of pigmented wool fibres. Shearers could recognise sheep with black-grey pigmented skin spots in the fleece area (Figure 23) and the fleece wool should be kept separate from unaffected lines. Cull (for slaughter) sheep showing black skin spots in wool-bearing areas. Fig 23. Old-age – black skin spots with pigmented wool fibres. The sheep was 8.5 years old and shorn 3 months previously.

Dark and Medullated fibre risk scheme

The Code of Practice (AWEX 2007) provides guidelines for the preparation of Australian wool clips. The woolclasser has a key role in quality assurance and new wool sale lot test certificate changes aim to identify wool that lacks this attention or is non-complying for other reasons (AWEX 2008). The Dark and Medullated Fibre Risk (DMFR) scheme (Hansford et al 2003; AWEX 2007) together with revised vendor declarations (http://www.woolindustries.org/dmfr.htm) was initiated by the Federation of Australian Wool Organisations due to inquiry and concern from the wool textile industry about increased problems with dark and medullated fibre. The DMFR scheme is based on a previous CSIRO proposal that made use of farm information to provide an insight to risk of urine stain and inherent pigmented fibre. The wool textile industry is making use of the DMFR information to assist in selection of wool lots for sensitive end-uses. Increased adoption of the DMFR scheme, together with other test developments in progress, should ultimately provide price incentives that encourage greater emphasis on producing low risk wool.

Conclusion

It is not possible to guarantee a complete absence of dark fibres in wool. It is practical to implement management and breeding schedules that will serve to minimise the risk for wool processors.

- Non-sheep dark fibres - minimised by avoidance of contacts with sheep and wool and general cleanliness as part of quality management schedules.

- Urine stain - minimised by removal within 3 months prior to shearing.

- Pigmented fibres – future occurrence is minimised by culling of affected sheep as soon as practical and perhaps also their parents (e.g. recessive black). Age is an important factor for inherited isolated pigmented fibres and associated types of visible pigmentation in young sheep and development of pigmented fibres in very old sheep.

Research projects in progress, where phenotypic information about visible pigmentation is being collected and analysed in conjunction with DNA marker studies, should assist selection practices in the future.

Acknowledgments

Author:

Malcolm R. Fleet

South Australian Research and Development Institute, Livestock Systems Alliance,

Turretfield Research Centre, Rosedale SA 5350, Australia.

E-mail: fleet.malcolm@saugov.sa.gov.au