Guidelines for characterising rainfall and water use efficiency

Guidelines for characterising rainfall and water use efficiency

Rainfall is a key determinant of pasture growth on your farm. To know the potential of your grazing land to produce pasture, you must understand the pattern of rainfall on your land. You can work this out by assessing historical rainfall records (for the farm, district or regional centre) and noting down the normal monthly rainfall distribution and the extent of variability from year to year.

Knowing the rainfall characteristics on your farm can help you to:

• Improve pasture growth and financial and environmental management through efficient use of rainfall in all seasons, particularly during periods of lowest pasture growth; and

• Reduce costs and maximise returns from pasture resowing, by selecting the most appropriate pasture species for the normal pattern and variability of plant-available water and sowing at the right time.

Water balance

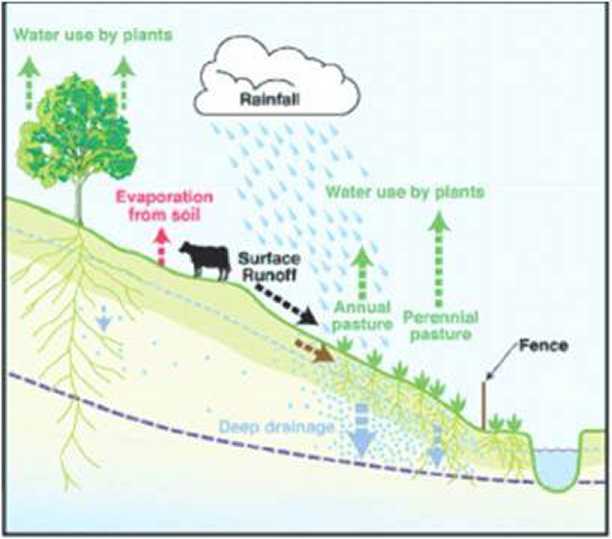

To maximise the potential of rainfall in a grazing system, it is necessary to understand the water cycle and what happens to rain after it falls (see Figure 1).

The following equation:

Water balance = P – (E + R + D)

Where:

• P= Precipitation

• E = Evapotranspiration

• R= Surface run-off

• D = Drainage out of the root zone

For short-term calculations (ie less than one year) an additional term is added to the equation to account for changes in soil water storage (this term is positive if the soil wets up over the period of calculation and negative if the soil dries out).

Temperature is another major influence on pasture growth potential. Unlike rainfall, it varies only slightly from its normal seasonal pattern throughout the year. Its major impact is on pasture production as all species have different upper and lower limits for growth. It also needs to be considered when selecting new temperate pasture species.

While sunlight is a critical element in plant growth, it is not considered to be a climatic variable that limits plant growth in southern Australia. Physical disruption of sunlight through slope and aspect (south facing slopes) is a factor. It increases in importance with increasing latitude. Growth and quality can also be limited through shading from other and in pasture utilisation practices.

Plant-available water (PAW)

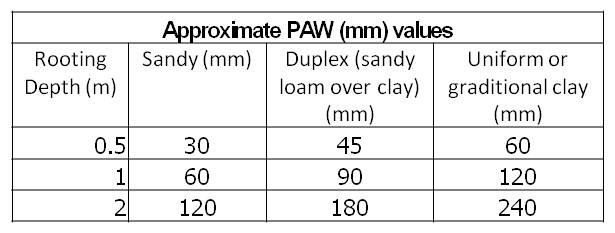

The latest research has demonstrated that differences in annual pasture production are much better explained by the variation in plant available water (PAW) than by total rainfall. Plant-available water depends mainly on texture (clay content), the ability to hold water and rooting depth. By understanding soil texture and rooting depth, you can compile a table of approximate PAW (mm) values (Table 1) or estimate PAW directly measured using soil moisture monitors. The use of soil moisture monitors is not likely to be widely adopted in grazing systems until producers know how to use the information to make more money and reduce risk.

Table 1: Examples of plant available water PAW (mm) in soils of different texture and for different rooting depths.

The soil PAW is a function of both plant rooting depth and the soil moisture storage capacity. This combination determines how much water can be held in the root zone available for plant use. Rooting depths range from:

• 0.6m to 1m for sub-clover, annual and perennial ryegrass

• 1.5m to 1.8m for perennial pasture grasses

• Over 3m for lucerne, chicory and trees

Deep, heavy clay soils can take in and hold a lot of water (ie these soils have a large PAW) allowing a perennial pasture to use up to 100mm/year more than on a sandy soil. Lighter, sandy soils not only have a small PAW, but also tend to have very high infiltration rates. This results in little or no run-off, greater deep drainage and pasture plants wilting more quickly between rainfall events.

In southern Australia, the more common duplex soils tend to have a balance between drainage and run off. In the northern, summer rainfall zone these same soils produce a lot of run-off and very little deep drainage.

Water use efficiency (WUE)

Water use efficiency (WUE) is a measurement used to assess the opportunities for improved pasture growth through better soil nutrition and pasture composition . Knowing rainfall variability and water use efficiency makes it possible to manage soil fertility, pasture composition and grazing management to maximise the use of rainfall for pasture growth.

Water use efficiency is simply an indicator of the amount of rainfall (water) that is converted into plant growth.

Applying information about water use efficiency

Knowing rainfall variability and water use efficiency allows you to manipulate pasture species and soil fertility to achieve the best spread of pasture growth across grazed land in all seasons. It also enables you to anticipate and act to prevent under-and overgrazing when there is a high probability of rapid growth (eg in spring) or low growth (in winter).

• Undergrazing results in shaded pastures, lower growth rates and lower water use by pastures, which can lead to increased water loss through deep drainage.

• Overgrazing results in high rainfall run-off, poor infiltration rates and high evaporation caused by inadequate ground cover, low litter levels, surface crusting and poor soil permeability.

Understanding water use efficiency enables you to implement methods to improve soil water-holding capacity, such as building soil organic matter. This leads to reduced rates of deep drainage and pasture growth when soil moisture moves below the root zone.

Pasture composition and soil fertility have a major influence on water use efficiency. Good grazing management in the following areas can lead to more efficient water use and therefore higher rates of pasture growth:

• Ground cover reduces run-off and protects soil from erosion. Depending on rainfall (pattern and intensity) and soil type, maintain at least 70% ground cover (including leaf, dead and litter material plus dung) on grazed lower to middle slopes (land class 3); and, a minimum of 100% on non-arable upper to steep slopes (land classes 4 and 5).

Surface ponding and evidence of run-off indicate crusted or impermeable soil surfaces that lower rainfall infiltration rates. Tool 1.7 describes how to measure ponding and run-off.

• Erosion or sediment deposits are further indicators of the need to apply management to slow or reduce run-off.

• Organic carbon (as measured in routine soil analysis) should be maintained above 3% and up to a maximum of 12% of soil content to ensure improved soil water-holding capacity.

• Soil biota (presence of living organisms) generally improves soil health and structure. This benefits water-holding capacity and infiltration rates, as well as helping to mobilise soil nutrients for uptake by plants.

Use the following strategies to improve and maintain water use efficiency:

1. Adopt tactical grazing (a range of grazing management methods) to meet animal production targets and pasture objectives at different times throughout a single year or over a series of years.

2. Assess soil nutrient status, and take corrective action where appropriate.

3. If soil nutrition status is within critical limits, assess your pasture utilisation and soil surface management, and take the appropriate action.

4. Anticipate periods where analysis of annual rainfall patterns indicates an increased risk of overgrazing (low pasture growth rates) together with high- intensity rainfall events.

5. When pasture utilisation, soil nutrition and soil surface management are within the guidelines for maximising water use efficiency, or your analysis of rainfall against the pattern of pasture growth indicates that current pastures are unlikely to achieve the best possible seasonal growth throughout the year and evaluate the pasture composition.

Tactics for managing the soil surface:

• Maintain growing pastures near the start of growth phase II (about 1,000kg green DM/ha) for as long as possible to aid regrowth. This has the added benefit of ensuring the highest possible pasture quality for grazing stock.

• Maintain (or increase) ground cover to manage run-off by removing stock before minimum pasture mass limits are reached (1,000kg DM/ha).

• Aim for medium to high levels of litter (at least two or three handfuls in a 30cm x 30cm area) to increase soil organic matter, protect the soil surface, decrease evaporation and increase water-holding capacity. Litter is preferably actively decaying plant matter, not old and inert material.

• Manage grazing practice to increase litter quality and breakdown rate.

• Encourage build-up of soil biota to improve soil structure (increased porosity or aeration), the rate of litter breakdown and incorporation of surface organic matter by avoiding excessive cultivation and the application of soil biota- reducing chemicals.

• Avoid grazing when soil is waterlogged and pugging is likely to occur.

• Develop stock containment areas to remove stock from at-risk grazing areas.

• Change the pasture composition to deep rooted perennials that will ameliorate soils with declining structure.

What to measure and when

Use historical rainfall records to assess the normal monthly pattern and variability of rainfall throughout the year before beginning a program to improve pasture growth and quality.

• Collect and analyse records for each farm or farm sector where rainfall might be different across the farm. Where these records are not available obtain district or regional centre information from local sources as the starting point.

Assess water use efficiency annually. Also collect the following measures from all pasture zones where water use efficiency is monitored:

• An estimate of daily pasture growth rates (kg DM/ha/day) for native and improved perennial pastures;

• The percentage of ground cover and bare ground at the start and end of the growing season;

• The mass and quality of litter – aim for at least two or three handfuls in a 30cm x 30cm area;

• Any evidence of soil erosion or sediment deposition – observe routinely after rain;

• The rate of surface ponding of water and run-off to dams – at least once every three years;

• The organic carbon content (%) at increasing depth – initially and then every three years and;

• Test soil for density or penetration with a penetrometer.