Sick birds should be treated as soon as possible, or removed from the flock. The presence of sick birds may compromise the ability of the flock to resist disease, by causing the disease to build up beyond the threshold level.

Sick birds should be treated as soon as possible, or removed from the flock. The presence of sick birds may compromise the ability of the flock to resist disease, by causing the disease to build up beyond the threshold level.

Dead birds should be removed from the shed as soon as possible, and disposed of in a manner that complies with environmental guidelines. Immediate burial (following EPA guidelines), incineration or composting is preferable.

DEAD BIRD COMPOSTING.

The composting process/apparatus should be able to accommodate the normal mortality rate of layers with up to 0.2% mortality per day. For example, in order to compost 500 kg of dead birds on the farm, a composter 2.4 m wide, 1.5 m deep and 1.5 m high would be required. The general rule is to build 0.06 m3 of primary capacity bins and 0.06 m3 of secondary capacity bins for 1 kg of dead poultry.

Commercial composters are available and can be hired or purchased.

For proper composting, four elements are necessary:

1. proper nutrient mixture of carbon and nitrogen (C:N range of 1:20 to 1:35);

2. 40–60% moisture;

3. a temperature range of 57°C to 63°C;

4. pH in the range of 6.5 to 7.2 (mildly acid to neutral).

The materials required are water, straw, woodchips or sawdust, dead birds and poultry litter.

When done properly, composting does not generate an odour.

Rodents, cats, dogs, feral animals, scavenging birds and flies must be kept away from composting carcasses.

The composting area should be away from sheds and boundary fences.

The composting area must be kept neat and clean at all times.

Details on the Australian Standard™ for Composts, soil conditioners and mulches (AS 4454-1999) are available from Standards Australia (www.standards.com.au).

Dead bird pick-up by a contractor should be avoided if possible; however, if a contractor is used and birds have to be stored prior to pick-up, they should be stored in a freezer.

DEAD BIRD COLLECTION

DEAD BIRD COLLECTION

Dead birds must be removed from the free range enterprise daily, or twice daily if mortality is high.

Once collected, dead birds must be moved from the free range area to an appropriate site either on or, preferably, off farm, for processing or subsequent collection by a contractor.

If dead birds are not disposed of daily, they must be stored in a designated freezer on the farm. The freezer should have sufficient capacity to adequately handle 1–3 days of normal flock mortality, and should not be used for any other purpose.

The dead bird collection area should be as far away from the shed site as possible; it should also be secure, and designed in a way that minimises the spread of infection. If possible, vehicles collecting dead birds should not enter the farm. If they must enter the farm, they should not come close to the flocks. For example, a dead bird collection shed could be provided, on a concrete base with doors on both sides. One door would be for dead birds to be placed in the shed, and the other for dead birds to be taken out and placed in the collection vehicle. The truck loading area should be washable.

Steps should be taken to minimise the presence of flies in dead bird collection and disposal areas.

Any dead bird collection containers must be washed and disinfected before being returned to the farm/shed area.

Personnel disposing of dead birds should be instructed on the need to maintain personal hygiene.

In the case of dead bird pick-up, the collection area should be as far away from the operational area of the farm as possible. The collection vehicle should not enter the farm.

Regular cleaning and disinfection of carcass storage containers and the collection area should be undertaken, to minimise the spread of disease by flies.

.

If water treatment is necessary (e.g. where the water supply is surface water or poor quality bore water), the efficiency of the treatment facility needs to be regularly monitored. When chlorination is used, a chlorination record chart should be utilised to document that the water has been adequately treated.

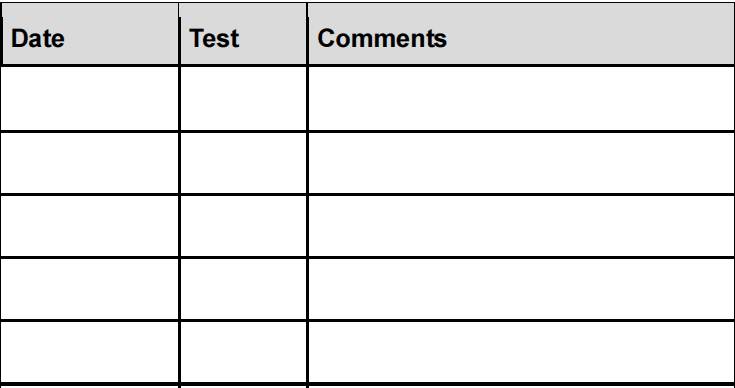

CHLORINATION RECORD

Chlorination requires a level of 5 ppm chlorine over the 1–2 hours holding time (contact time).

Drinking water, like feed, should be accessed inside the shed; or, if watering stations are required outside, they should be of a type that cannot be easily accessed by wild birds (e.g. a nipple system). It is important to place any outside watering system in a cool area, as chickens will not drink hot water.

The watering system should be maintained, in order to prevent leakage and the creation of wet patches within or outside the shed. Wet areas may result in a build-up of flies, provide an ideal environment for bacterial multiplication, and may also attract wild birds.

Water tanks should be checked regularly to ensure that they remain bird-proof.

Rodents.

Baiting stations should be placed around the farm perimeter in a secured manner that allows access by rodents and prevents access by other animals. Narrow pipes are ideal for this purpose. The baiting stations should be checked weekly, and fresh bait placed monthly (or more often if required). An activity logbook for rodent control should be maintained (see Appendix 6). It is recommended that baiting stations be placed at intervals of 10–15 m around the perimeter, or outside the sheds.

Feed spills must be cleaned up as soon as they occur.

In most free range enterprises, long grass should not be an issue around sheds, as chickens tend to take care of this aspect themselves. If this is not happening, however, the grass around the shed site should be kept cut, as long grass attracts rodents, and favours the survival of bacteria and viruses.

Visitors.

Many egg farms sell eggs and manure directly to the public. In such cases, every effort should be made to stop customers entering the free range area. Free range farms are more vulnerable than conventional sheds to contamination by visitors. People can carry contaminants on soiled footwear, and these can persist in the soil for many weeks or months.

Neighbours, friends, sale representatives and other people should be kept away from the free range area unless their presence is essential.

Visitors who are required to enter the free range area (e.g. veterinarians, maintenance and service personnel) should be recorded in the visitors’ book and asked to sign a visitor declaration unless an emergency exists

LAYER FARM ENTRY PERMIT

Authorisation for: _________________________________________________________

Date of entry: _____________________________________________________________

Terms and conditions of entry to layer sheds

Visitors:

• have not been in contact with any avian species or untreated poultry manure within the last 24 hours.

• agree to wear the protective clothing required, or their own unused clothing.

• agree to wear the protective boots or overshoes provided.

• agree to sanitise their hands in the facility provided.

I agree to the terms and conditions of entry stated above.

Object of visit: ____________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________

Name________________________________ Signature___________________________

Producers may insist that visitors who have visited other farms on the same day do not enter the sheds or range areas.

Visitors entering the free range area shed should be provided with protective clothing, if they do not carry their own set of unused disposable protective coverings. The protective clothing should include overalls and plastic overshoes or boots. In general, every farm should have sufficient protective clothing for 2 to 3 visitors.

Tools taken into the free range area must be clean and free of organic matter and dust.

Any crew delivering pullets or day old chickens to the farm should sign a declaration that they have not been on another farm on that day (i.e. split delivery). If it is not possible to avoid split deliveries, the delivery crew should shower and completely change their clothing before being allowed into the free range area sheds.

Any crew picking up end of lay hens for processing or transfer to another farm should comply with the same conditions as above, unless they are depopulating the entire farm.

The drivers of feed delivery vehicles who are required to enter the free range area or feed mixing area should be provided with disposable plastic overshoes if they need to get out of their vehicle, particularly in the area where feed is mixed.

Customers should never be allowed to enter the free range area to collect eggs.

Maremma guard dog.

Other animals.

Maremma guard dog.

Good fencing is required around free range enterprises, to prevent entry by animals such as dogs, foxes and cats. In many situations, however, fencing alone is insufficient to stop such intrusions; therefore, some free range enterprises keep specially-trained dogs with the chickens, as protection against other animals, and also against unauthorised human entry.

Guard dogs such as these are not regarded as a biosecurity risk, but rather as a biosecurity tool.

Hygiene.

Hygienic conditions on the farm and in the egg storage and grading facilities will minimise the risk of bacterial contamination of eggs. It is recommended that free range farms:

• keep the farm and egg grading room clean and tidy at all times;

• control rodents and flies on the farm, particularly in the egg grading facilities;

• make sure employees are familiar with the basic principles of food hygiene – an operational manual with a checklist of routine hygiene and husbandry standards is recommended;

• make sure the egg belts in automated systems are clean and properly maintained, as dirty egg belts have the potential to dirty numerous eggs;

• regularly remove cobwebs and dust from inside the shed and egg grading room;

• use new, clean egg fillers;

• don’t allow domestic animals inside egg grading rooms;

• clean manure flaps under cages and regularly clean nest boxes in barns;

• maintain a record of the checks you do;

• ensure manure/litter in the shed is low in moisture, as the moisture content of litter/manure is an important factor in the multiplication of some bacteria.

Author.

George Arzey and Ian Littleton