Crossbreeding is an effective method of improving efficiency of production in commercial cow-calf herds. However, commercial cattle producers should study crossbreeding systems and evaluate them before deciding which one is suitable for their environment and resources. Criteria for Evaluating Crossbreeding Systems outlines basic properties of crossbreeding systems to keep in mind when considering a program.

Criteria for Evaluating Crossbreeding Systems

- Level of hybrid vigour (heterosis)

- Merit of component breeds

- Complementarity

- Consistency of performance

- Deals with genetic antagonisms

- Meets end-product target

In general, crossbreeding systems fall into 2 categories, those that produce replacement females as well as market cattle (rotational & composite systems), and those that produce only market cattle (terminal cross). In rotational (or composite) systems, bulls must be selected with maternal traits in mind as well as growth and carcass traits, since replacement heifers are retained from within the herd.

Terminal systems allow for greater emphasis on selection for growth and carcass traits in bulls since female replacements are supplied from outside the herd. The genetic merit of a terminal bull for maternal traits is of no consequence since his female progeny will not be bred. Calving ease must be considered regardless of the type of crossing system.

Rotational Systems

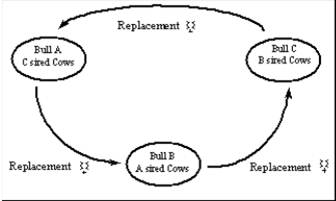

The rotational system requires establishing two or more breeding herds. In a two-breed rotational system, two groups of crossbred cows are established. Cows sired by Breed A are mated to males of Breed B, and females sired by Breed B are mated to males of Breed A. In a three-breed rotation, a third breed is added to the sequence (Figure 1). In rotational systems heterosis is retained at high levels, 66% in two–breed rotation, 86% in three–breed rotation.

However, fluctuation in breed composition between generations can result in considerable variation in level of performance among cows and calves, unless breeds used in the rotation are similar in performance characteristics. Use of breeds with similar performance characteristics restricts the use that can be made of breed differences to optimize breed complementarity.

Figure 1 Rotational System (3-breed)

Crossbred (Hybrid) Bulls

Hybrid bulls offer an alternative method of rotational crossbreeding. Using F1 bulls or composite bulls in rotational systems can significantly reduce intergenerational variance, especially if breeds chosen to produce F1 bulls optimize performance levels (ie. breed complementarity) in their crosses (i.e. continental X British). Using F1 bulls consisting of the same two breeds as the crossbred cow– herd but unrelated can result in retention of 50% of maximum possible heterosis. Supply of performance tested F1 bulls from selected and proven purebred parents may be limited.

Rotate Sire Breed

The rotation of sire breeds every 2 to 4 years provides similar benefits to a rotational breeding system for producers with small herds and limited breeding pastures. The result is simplified management, and individual and maternal heterosis. Disadvantages are the increased intergenerational variation and reduction in heterosis as breed makeup of females’ swings more toward one breed and back again. This can be minimized if the breeds utilized are similar.

Rotating F1 males every 2 to 4 years can help reduce intergenerational variation but maintain complementarity if appropriate breed crosses are selected. By rotating different breeds of F1 bulls (AB, CD, EF, etc.) every 4 years, you can avoid wide intergenerational swings in biological type, if breeds A, C and E are similar in type as are breeds B, D and F.

Terminal System

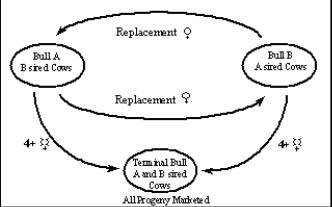

In a terminal system (Figure 2) all calves are marketed and replacement females are purchased from outside the herd. This allows for more intensive selection for specific traits in the male and female lines used in the cross. Cows are usually selected for moderate frame, good milking and mothering ability. High growth potential and good carcass characteristics are important in the male line.

Heterosis benefits will be maximized when a crossbred cow (F1 female) is mated to a sire of a third breed. In a terminal system females are selected to match environment and resources while males are selected to meet end product targets (i.e. growth and carcass). High degree of complementarity and consistency of progeny is possible. Replacements need to be purchased and are price and availability dependent.

Figure 2: Terminal System

Figure 3 Rotational-Terminal

Rotational Terminal

Figure 3 demonstrates a rotational terminal system. This system combines the best parts from the traditional rotational systems and the static terminal sire systems. The rotational part of the system provides replacement females while the terminal sire part of the system allows most of the marketed calves to be sired by growth carcass type sires. Cows remain in the rotational part of the system until they reach 4 years of age and then they move to the terminal part of the system. However a large herd size is required (at least 100 cows).

Composites

Definition:

“A population made up of two or more component breeds, designed to retain heterosis (hybrid vigour) in future generations without crossbreeding with other breeds.”

Composite cattle are hybrid cattle that breed to their own kind, retaining a level of hybrid vigour we normally associate with traditional crossbreeding. Management requirement of a composite herd is similar to a straightbred herd, substantial heterosis can be maintained in composite populations so long as adequate number of sires are used in each generation to avoid inbreeding.

Heterosis will vary depending on the number of breeds that were used to form the composite. It can range from 50% of maximum possible heterosis for a 2–breed composite to 87.5% for an 8–breed composite. Selection of breeds going into the composite is also critical. Breed differences should be fully exploited so as to match the composite with the environment in which it will be used and to match it with market specifications.

Composites have the potential for “standardizing” commercial cattle, thus reducing the variation we currently see in market animals. Problem cattle today, from the feedlot and carcass perspective, are biologically extreme breeds. These extremes in market cattle are due to purebreds, high percentage animals from extreme breeds or crosses of similar extreme breeds. Often the result of poor crossbreeding decisions. With a composite breed, crossbreeding decisions are made when the breed is formed. Commercial producers just need to choose what composite breed to use. Composites are expected to be complete and balanced in performance and only those composites that fulfill this expectation are expected to survive.